Youth sports participation today has become more popular than ever. It is estimated that approximately 10 million high school age students participate in extracurricular athletic programs in the United States. If you take into account all sports participants from age 6 to 18 years of age, the number more than triples to approximately 32 million as reported by the National Council of Youth Sports (NCYS) in their 2000 census. And based on current trends, it is more than likely that these numbers will not be decreasing anytime soon.

Youth sports participation today has become more popular than ever. It is estimated that approximately 10 million high school age students participate in extracurricular athletic programs in the United States. If you take into account all sports participants from age 6 to 18 years of age, the number more than triples to approximately 32 million as reported by the National Council of Youth Sports (NCYS) in their 2000 census. And based on current trends, it is more than likely that these numbers will not be decreasing anytime soon.

Along with this increase in popularity has come a slew of articles discussing a variety of issues in youth sports, not the least of which centers on the loss of “fun” in sports participation for kids. You would be hard pressed to find any information (whether in a book, on the internet, or in your local newspaper) raising concerns over youth sports involvement that doesn’t mention the word fun somewhere, at least from the perspective of “loss of” or “need for” it. What I find most interesting is that few, if any, make an attempt to define what fun really means in sports. It is simply taken for granted that if it is not fun, it is not good, and if it is fun, it is. However, this leaves me with two more pressing questions, what does having “fun” really mean when it comes to sports participation and where does this “fun” come from?

These very questions draw my attention to several past comments made to me over the years by parents of, predominantly, collegiate athletes. Many of these interpretations, based mostly on their kid's experience, centered on the idea that sports (especially college sports) for their competing athlete had become like a job to them. That the time and effort they were, or had been, putting in had literally become “work”, and not the term work as in extra effort but work as in occupation. Basically, that playing sports for their young adults was not fun anymore. Even some college athletes (or their former high school coaches) that I have personally spoken to echo similar complaints. Some express their current dissatisfaction with their college sports experience, others leave college sports behind before their eligibility ends, and still others decide to never play their sport again. All because it is not fun anymore.

These very questions draw my attention to several past comments made to me over the years by parents of, predominantly, collegiate athletes. Many of these interpretations, based mostly on their kid's experience, centered on the idea that sports (especially college sports) for their competing athlete had become like a job to them. That the time and effort they were, or had been, putting in had literally become “work”, and not the term work as in extra effort but work as in occupation. Basically, that playing sports for their young adults was not fun anymore. Even some college athletes (or their former high school coaches) that I have personally spoken to echo similar complaints. Some express their current dissatisfaction with their college sports experience, others leave college sports behind before their eligibility ends, and still others decide to never play their sport again. All because it is not fun anymore.

I can distinctly remember not being able to relate to these statements and being perplexed and confused by them. It was just so different for me. When I look back at my own experience as a high school and collegiate athlete, those types of thoughts never entered my mind. Sure I remember working hard and forcing myself to train and condition (my conditioning was extensive) at intense levels, and with high expectations, but I cannot remember one time where I felt like what I was doing was like a job, and I spent a lot of hours in the gym. I'd say around 5 hours a day 6 days a week. If it was possible, I would have continued 4 more years of collegiate competition, and the training that went with it.

For some reason, my perspective (or frame of reference) was completely different. I just never looked at my experience in the manner that the earlier examples demonstrate. So the big question then becomes, what made the difference in my perspective versus theirs?

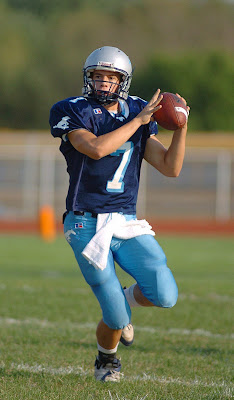

Before I answer this, at least from my vantage point, let me talk a little bit about what I think makes sports fun to play. For younger participants, the key word is the last word used in my previous sentence “play.” That is what kids like to do, and that is what I liked to do, just play the game. You ask younger elementary school kids what their favorite class is and most will say physical education (or recess), at least that is the impression you get when you watch them in a physical education class at that age level. To them, just playing the game for the sake of playing is fun.

At some point, and I do not know exactly when this happens or the best time for it to happen (however, I do think this is very individual in nature), the competitive aspects of sports will become more important to an athletic child. Just playing the game will, and should, always be part of the fun in sports (it is part of developing and deepening a “love for the game”) but sooner or later a young competitive athlete themselves will want to become better or good at what they are doing, and they will derive less or more enjoyment out of playing sports based on their feelings about this. I know I did. In fact, I believe that where I learned to place my focus and what I decided was most important to me, with regard to competitive sports, had a great deal to do with my feelings about my own sports participation (not getting burned out or looking at it like a job), and in turn, any level of success I had.

At some point, and I do not know exactly when this happens or the best time for it to happen (however, I do think this is very individual in nature), the competitive aspects of sports will become more important to an athletic child. Just playing the game will, and should, always be part of the fun in sports (it is part of developing and deepening a “love for the game”) but sooner or later a young competitive athlete themselves will want to become better or good at what they are doing, and they will derive less or more enjoyment out of playing sports based on their feelings about this. I know I did. In fact, I believe that where I learned to place my focus and what I decided was most important to me, with regard to competitive sports, had a great deal to do with my feelings about my own sports participation (not getting burned out or looking at it like a job), and in turn, any level of success I had.

There came a point in time (occurring when I developed those feelings of wanting to be good) that I started to place a higher level of importance on how good it felt to perform a skill well. I am not talking about the adulation one receives from others when hitting a home run in baseball, hitting an ace serve in tennis, or a spike in volleyball, but the actual positive internal feedback one gets from performing a skill at a higher level of competency than what one normally performs. For example, the sound and physical feeling one gets from the crack of the ball off the exact sweet spot of the bat in baseball knowing it was a good hit before it even leaves the bat, or the same feeling from a tennis serve as it comes off the sweet spot of the racquet, or the perfect approach, timing, technique and crushing of the ball on a spike in volleyball. These types of intrinsic feelings, for me, became so strong that they developed into the main focus of my training, and the fun behind why I competed. Don’t get me wrong, I loved to win and hated to lose; it was just that I placed a much higher priority on trying to master and perfect skills, and perform those skills in competition, than just winning the competition itself. I loved the feeling of moving and catching a tough ground ball right in the center pocket of my glove in my younger days of little league, and hitting a solid forehand or backhand in tennis executing the appropriate spin for the shot (one reason why I still play tennis), and performing a swinging movement in gymnastics without any wobble or extra swing in the still rings event. This was where I derived my enjoyment, or fun, from playing and competing in sports, and it is where I developed a true understanding of the intrinsic value behind my own sports participation. What this type of perspective did was allow me to enjoy my athletic experiences based solely on aspects that I controlled; they were intrinsic. I placed less importance on the win itself and more importance on the process, which, in turn, greatly increased my chances of reaching my potential.

This type of perception is a point of view that I do not see held by many and thus, is not stressed as a focus in youth sports today, and it should be. Younger athletes should be encouraged to take great pride on being able to accomplish, improve on, or master something today that they could not do yesterday. It should be of primary importance and take precedence over emphasis on any one win or competition. Doing so will place winning right where it should be, as an outcome of the efforts you put in, and allow young athletes to truly enjoy their sports experiences for years to come.

Photographs provided by: Richard M. Cook, Frank Angileri, and Bill Hois

Kirk Mango

Becoming a True Champion